Newsletter

Sign up and stay in-the-know about The Crowd & The Cloud and the world of citizen science.

My name is Russel Honoré, Lieutenant General United States Army, retired. I was born and raised in Louisiana, in a little place called Lakeland, about 125 miles north of New Orleans. I spent 37 years in the Army.

I spend most of my time now doing public speaking about leadership and preparedness in the new normal. I've written two books, "Survival" and "Leadership in the New Normal." I spend my volunteer time, about 70 percent of my waking hours, working with poor communities in Louisiana that are being affected by both air and water pollution. I do that under the brand “The Green Army.”

Can you describe the environment and culture of the area?

I grew up on a small subsistence farm in Lakeland. I was the 8th of 12 children. It was a relatively poor community, small farmers getting by. My parents were of the last generation of farmers in our family, as well as most of the community there. But it was a good life. We went to Rosenwald High School, a segregated school system in south Louisiana, and from there I was the first in my family to go off to college at Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in 1966. And in January of '71 I got my commission as a 2nd Lieutenant in the infantry, and my degree in Vocational Agriculture. At that time, I had an obligation to go in the Army, because we still had the draft going. And what started off as an obligation ended up as a 37 year, 3 months, and 3 day career in the military.

Emergency crews fight flames erupting from the BP Deepwater Horizon oil rig.

Can you tell me about the Deepwater Horizon oil spill?

First of all, I don't call it the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. I call it what it is, the “BP oil spill,” which I found was a pretty ingenious act by BP to call it “Deepwater.” And then the press called it the Gulf oil spill, and I challenged the press many times to call it what it was, which was a British Petroleum, “BP oil spill.”

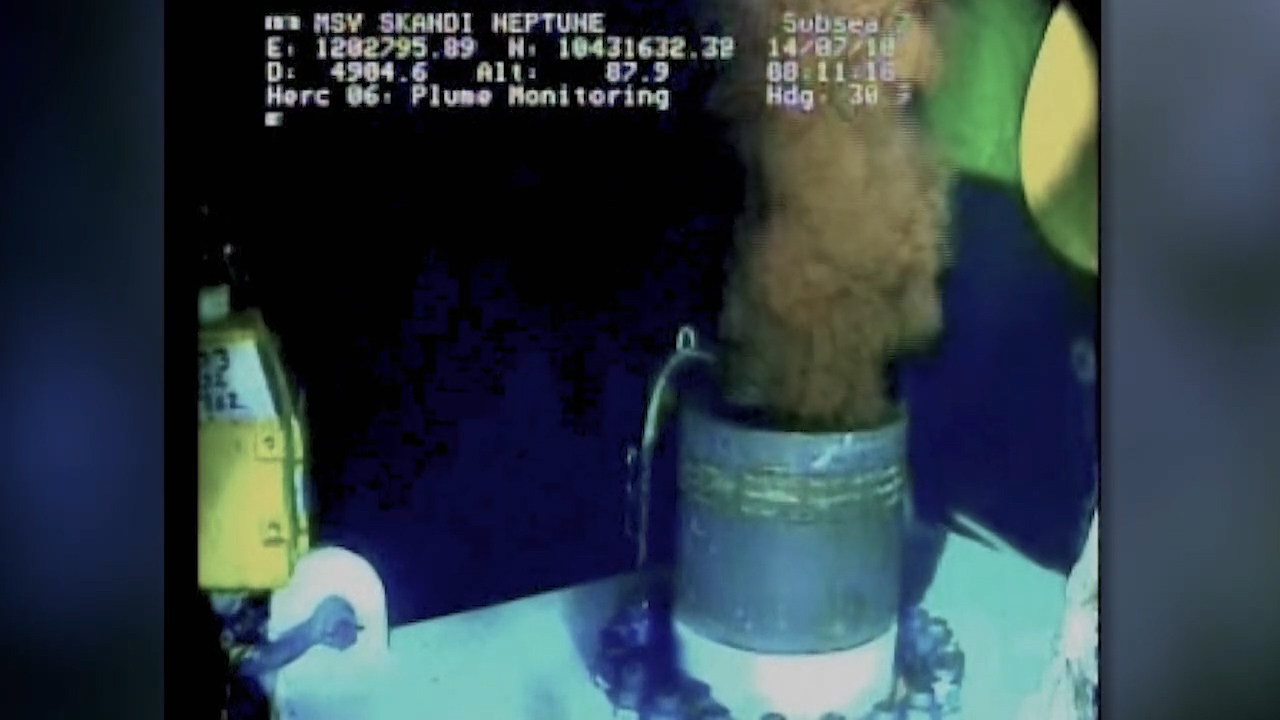

That oil spill, as I recall, it kind of slow-rolled on the people in Louisiana, because the immediacy of the moment was obvious; within hours 11 people had lost their lives. We were surprised that they were doing what they were doing at such depths, and not only that the primary plan didn't work, the backup plan didn't work. And come to find out, they didn't have a backup plan, and that they were able to do all this with the government standing around kind of twiddling their thumbs. If you ride down the road with your seat belt not on, some cop will stop you, and give you a ticket. Yet these idiots are fooling around in the ground at thousands of feet deep, and the outcome of an accident just literally ruined a whole region, let alone all of Nature's creatures that live in that water. You know, the old saying that we all grew up with, oil and water don't mix? Duh! And they're doing something that could jeopardize not only a large group of people who make their living in the Gulf, but the audacity to do it and put the entire Gulf at risk.

The Gulf of Mexico, we live here, so we're kind of like sentinels. We really watched what's happening there. You know, we get about 35 percent of our fresh seafood from it, or we used to, and a good bit of oil is explored out there in various places. But little did we know that so many people were taking so much risk with so little response capacity.

The whole thing was a debacle from minute one. And I grew up in the Army, when we did high risk operations, and we've been doing this for two decades. When they described BP, when they spoke publicly about what they were doing, they were obviously right inside a high-risk mission. This final phase, as they described it, of getting after that oil and getting pieces of equipment and things.

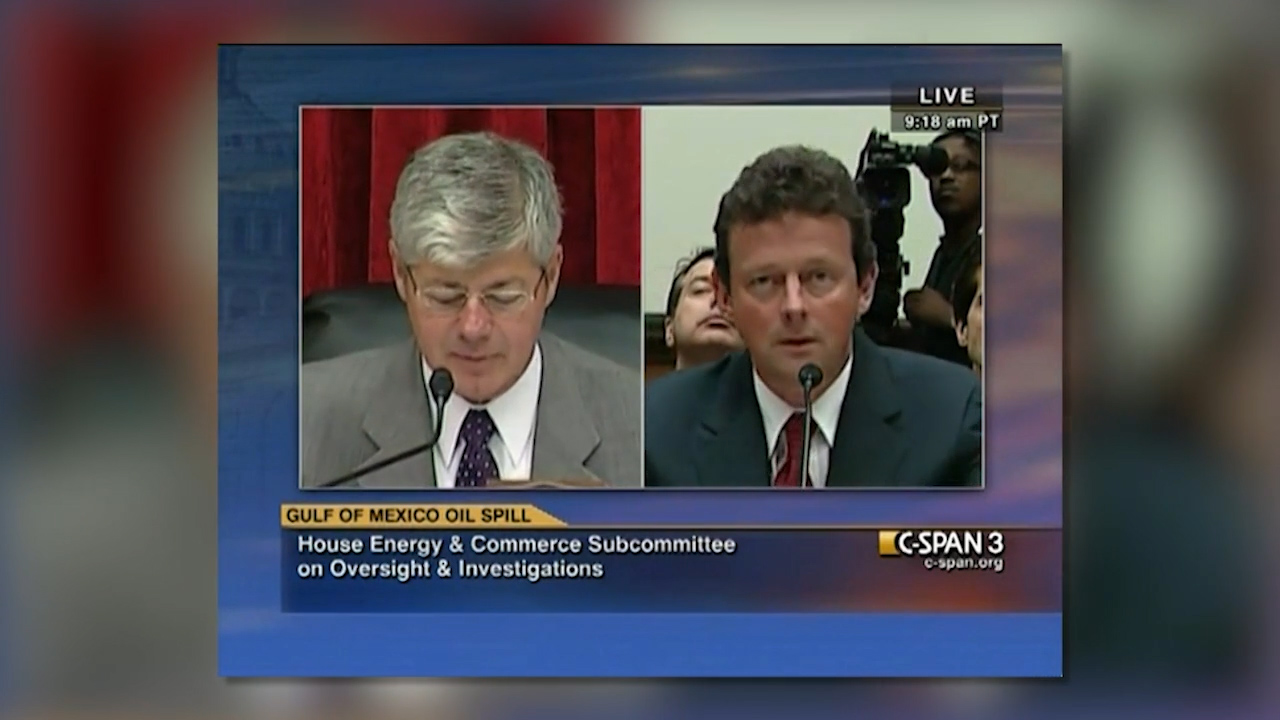

For the CEO to say he didn't know about it, that's just unbelievable! You could destroy the Gulf of Mexico, and the CEO... well, what is the CEO paid for? I mean, it puts CEOs in a whole different category with me, because most of them bullshit about where to go play golf, what resort they went to, and you know, how much bonus they make. That guy, Hayward, puts them all in a category that makes you think about how much they really know what's going on in their companies.

So, that BP was an awakening to me from the risks that they were taking, and it wasn't just about them losing money after the well didn't go in. It's that the consequences of the mistake, which we still see today five years later, are evident. There's still tar balls coming up.

Then our response was equally discovery learning. Our work (involves) contingency plans for nuclear disasters, for enemy attacks, for pandemics: that's what I did in the military as a First Army Commander, and prior to that I commanded Joint Force Headquarters, Homeland Security. Prior to that, I commanded a division in South Korea, all that was around after North Korea's attack. And before that, I was in the Pentagon in charge of military response to civil authorities, scenarios like this.

And to see, after the disaster happened, the denial by the company, and the government is sitting around, "Well, we kind of didn't know what was going on." Well, wait a minute. What do you mean, government, you don't know what's going on? How, how could that be? I was in the government. That was our job. Then you come to find out, the government is so corrupt, the same things we do to a degree of specification, it boggles the mind. Comparisons. I was sitting with some farmers in south Louisiana after the BP oil spill. A lot of them used to grow their own calves to have their own meat. Well, this generation of farmers would take their calves to a local butcher, pick-up the chopped meat, and take it home. We grew up that way. As opposed to killing them out in the barn, like our grandparents did. So these farmers would tell the story of taking their calves to the butcher shop, and then there's only certain days the guy could kill pigs, and a certain days he'd kill cows, because there had to be a federal inspector there. I don't remember a bunch of Americans getting sick over that entity. But here we've got idiots with a company from England boring a hole in the freaking Gulf floor thousands of feet deep, and there's no freaking federal inspector there! But this pissant, small time butcher shop in Pointe Coupee Parish where I'm from has got a federal inspector. Why?

Oil gushes into the ocean deep in the Gulf of Mexico.

We're drilling a hole underneath the ocean, a place that Congress had allowed companies to go inside of US territorial waters. Thousands of feet deep. There's no federal inspector. How could that be? The CEO didn't know they were doing the operation. How in the hell could that be? The other thing Congress has done is that they've allowed these companies to operate in that space with a lot of federal immunities. They get years of tax breaks from exploring that oil. And they don't have to pay any until they've paid off the debt associated with drilling that well. What a good deal. What these companies will tell you if you invest with them is you make 70 percent profit.

So, here's a company, an industry that can make 70 percent profit and they're out there drilling in such a dangerous proposition. And there's no backup plan. There's no inspectors on site. It's a high risk mission. It really disturbed me on how industry is operating. It disturbed me that our government did not have what most people would consider proper supervision over what they were doing, and how they were doing it. And that because these people have a lot of political donation money, they are able to get lobbyists and have the government look the other way.

So in essence, this industry as we know it, the energy business, oil and gas, and don't get me wrong, I came in a car that used gas, probably came out of one of those wells. I know it's a necessary requirement. This is what we're using for energy now. But it doesn't give them the right to destroy the environment we're in. And my interest in BP was kind of the beginning of my being vocal about speaking out that they don't have a moral or legal right to expose the rest of the population in the area. As well as to put that much risk to wildlife and sea creatures with such a sketchy plan. That was very disheartening.

CEO Tony Hayward testifies before Congress.

What do you think about the impacts of industry and the promise of jobs, with no regard for the environment and the people that depend on it?

Companies that have a propensity to cause significant amount of pollution, chemical pollution from plants, refineries, exploration work, they run psychological operations on our community. And that psychological operation is "We're going to come in. And we're going to create a lot of jobs." Uh, that theory plays well with politicians. Because every 10 cent politician to the ones in the White House think their job is to create jobs. Now, where is that in the constitution? Where is that in the job description? I've heard the oath to the President and oath to every governor. There's no line that says create jobs.

But this idea of these companies coming in and saying, "We're going to create jobs, and, oh, by the way, we need exceptions and exemptions to the Clean Air and Clean Water Act because you need these jobs," it would be as if terrorist organizations came. ISIS would come to Louisiana and say, "Hey, we going to create jobs. Let us in." You know, that this mode of operation we've got, "Oh yeah, come on in, ISIS! You going to create jobs? Y'all come on in with your flying flag." That's how stupid we sound sometimes. I don't speak emphatically, I speak by the exception. Not everyone think this way, but so much of our population is conditioned to believe that this exploration is where it doesn't have an impact on our environment.

When my parents were young and when I was young, growing up in South Louisiana, we thought nature could heal anything that we threw at it. I remember we had a couple old tractors. Each year, as the wintertime came, we would pull those old tractors up and we'd open the cockpit on the radiator, the water would run out with antifreeze in it. And one day, we were doing that and a county agent came by and said, uh, "Hey, what are y'all doing? Don't let that out on the ground. It's going to get into bayou and it'll kill the fish." "OK, boss." He said, "Oh, by the way, don't let that oil on the ground, you capture that oil and you put it in old barrel. And when you get a barrel full, you take it to town. You'd get 50 bucks for that barrel of oil." That was a pretty good concept. So we started the concept of recycling oil. Up until then, we thought you put it on the ground, you throw a little dirt on it and Mother Nature would clean it up. I think we did a lot of things last century that we thought Mother Nature would take care of.

But then, in the early '70s, that started to come home on us in the post-industrial age. We saw cities like Cleveland where those rivers would catch fire, so we had to have the Clean Water Act. And cities in the US where you couldn't see. Most people remember Los Angeles steel mills up on the east coast with heavy fog. All that was happening until we got the Clean Air Act. We always thought, "Well, Mother Nature would take care of it. Well, wait till it rain or wait till a wind come through. It will go away." No, it's not going away. It's going somewhere else.

That message that industry brings jobs is paramount. Look, right here in Louisiana, we have what we call some “fenceline communities.” Where the asthma rate in these fenceline community… they are old communities, and over time, these parishes don't have zoning boards. So if you lived along the Mississippi river or anywhere south Louisiana, Louisiana has over 560 chemical plants. That's level five plants that have to be supervised by EPA standards because of the type of toxicity in those plants. We, on the other hand, say those plants make things we need, right? That computer you're holding is made from components that came out of some of these plants. It might be the paint or it might be the plastics.

That being said, it doesn't give them the right to poison our people either. Kids that live downwind from a coal-fired energy plant have eight times the asthma of kids who don't. Now, who do you think live near coal fired energy plants? It's not the rich kids. It's generally the poor kids. That's happening all over America, but it's happening profusely here in Louisiana because we have so much energy businesses that are built around this availability of natural gas and oil that prevalent in Louisiana. We are a hubzone. We are a transit zone for oil and gas. We're either shipping it out or we're shipping it in.

We are blessed to have the Mississippi River, which is a great mover of things from the interior of the United States of America. Some 31 states have access, and their water flows into the Mississippi River. To put that in context, and if you look at the end of the Mississippi River, there's a box out there. We call it the “dead zone.” It's 800 square miles. We lived the whole last century thinking that what goes into the river will flush out to the Gulf and everything will be OK. Now, scientists have discovered this 800 square mile dead zone. You might say, "Well, where does it come from?" Well, most of it comes from farm runoff. Some of it comes from the cornfields in the Midwest. Some of it comes from dairy farms where, when I was in high school, if you raised 90 bushels of corn an acre, the 4H club would give you a blue ribbon. Well, today, they are raising over 240 bushels of corn an acre. And the reason they do that is through the infusion of ammonia and nitrates.

Those excess ammonia nitrates products make their way in the streams and canals and toward the Mississippi River, and they end up in the Gulf of Mexico. And when they go to this area at the mouth of the Mississippi River, in the Gulf, in August, they create a giant algae bloom. When they die, they settle to the bottom and they destroy all the living organisms on the ocean floor. When you kill the plankton, it kills the beginning of the food chain. We've got to fix that. If we don't fix it now, in 30 years maybe that 800 square miles become 1,200 square miles.

LT General Honore after Hurricane Katrina.

The BP oil spill happened soon after Katrina. What did that do for the morale of people in Louisiana?

The back-to-back disasters, if I may term it that way, was challenging because we came out of BP and then three years later, we had Gustav come through and do tremendous damage. It didn't hurt the city of New Orleans any, much of the levee system had been repaired. The city fared well here. Gustav ended up pushing its way up toward Baton Rouge and turned the lights out in our capital city, which was an awakening for the people in Baton Rouge because they didn't experience much damage during Katrina. It broadened the level of resiliency across the South between Katrina and Gustav. The evacuation went well. Then two years after Gustav, five years after Katrina, we had the BP oil spill. That'd make you kind of scratch your head. Then, the year after BP oil spill, we ended up with Irene and then we had (hurricane) Ike go into Louisiana, Texas area. It was a real test of resiliency of the state and the parish governments to take care of people.

I think what Katrina did conditioned people to have a little bit of understanding of what needed to be done. So by the time that BP oil spill came around, people were pretty good at the natural disasters. The difference between a natural disaster and the man-made disasters, is that FEMA is not there. The government, for some reason, used contractors, as opposed to mobilizing FEMA, which would normally go into communities, and they had gotten pretty good at what they do, to try and take care of people. The idea was to put the burden on the company, British Petroleum, and let them deal with taking care of the people. I didn't like that model. And I was very critical of it. I didn't like the model that this was a Coast Guard response.

The Coast Guard are good at what they do. But operations like this was way too big. There's technology that could have been brought in. There's a lot of assets in the Navy, the Army, and the Marines that could have helped them with the response. The coordination of the cleanup effort was left to the state. And the offshore stuff was left to BP to work with its contractors. The Coast Guard was in monitor mode.

Oil spilled from the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster.

What do you think the role of citizens is in holding governments and corporations accountable to pollution?

Citizens have a big role. If you look at the role of citizens during BP and Katrina, most of the people's lives saved during Katrina were done by fellow citizens. When you see things like the BP oil spill happen in American communities, people want to get involved. Because that's been the tradition. If there's a tornado come to town, everybody go help. Save the lives, you pick up stuff, you help people get back. When BP happened it was like watching a bad movie where somebody didn't finish the script. They're making shit up as they go. And, that was somewhat disturbing.

Then there was access to information. As if they had some right to privacy; they were worried about liability. That was disheartening. And then you see citizens, many of them made their living, or the Gulf was a big part of their recreational life. They were either volunteering to go work in the cleanup, or volunteering to help take care of people who became sick from the disbursement (agent) that was sprayed out over the Gulf. And there are many reports of people allegedly getting sick from that. And we're in a dilemma here, because we rely on citizens during disasters. Neighbors helping neighbors. It's happened in every storm that happens. The citizens show up. They help one another. When you have an accident like the British Petroleum one, I think one of the things it has taught people is you need to make sure you got all the information before you go inside that hot zone.

What is environmental advocacy about for you?

We've got to put things in context when you talk about global warming, climate change, and environment. I kind of use them interchangeably because for whatever reason, they've become political talking points for our two primary parties. Last summer, during the United Nations Climate Change Conference in New York, Al Gore, who's in advocacy for climate change and environmental justice, asked me to come up because had heard about the Green Army and read an article that ended up in "Newsweek." He asked me, "Why don't you talk about climate change," I said, "Because we're standing in oil." It would be equivalent to a man drowning and you offering him a swimming class. It's too late. You got it?

I need to talk to you about standing in oil because that oil is creating the climate change. Are you with me? So, the pollution that we create in our communities, here in South Louisiana, where mostly people work in the energy business, try talk about climate change. Most of them have been conditioned that it's not good science. That's what people have heard their Dad say because their Dad hears their boss saying, and the association that they belong to has declared it not good science.

So, when I go into Houma, Louisiana, when I go into Abbeville, Louisiana or Lake Charles or Maurice, most of these economies run all from big oil. I don't talk to them about climate change. I don't talk to them about solar power. I talk to them about the places they used to go fish that they can't fish there no more because there's no fish left. I talk to them about going to places in the wetlands that are underwater now and why they're underwater. People can relate directly to pollution in their community and everybody can do something about pollution.

Every time I see a Styrofoam cup, I get pissed to no end. Because that thing's going to be on this Earth for 100 years. And we don't have no need to use it. We know better now. When we first started using it, 30 years ago, we thought it was a miracle product. But it doesn't go anywhere. It comes, we create it, and there's nothing you can do with it. And we're still creating it. It's crazy. So, there are things that we do that don't make sense and we continue to do them.

I talked to a guy about going crawfishing inside the Atchafalaya. And they tell you stories about places you can't go, but you should be able to go because the state controls every navigable water body. Well, big companies go out there and they block those navigable waters off. They say, "We're doing a temporary construction project." And (you) come to find out they did it right before duck season, so they could flood that area with water. When you flood an area that may get water four or five days a year, when you flood it for two months, guess what happens? You change the ecology of that ground. So, this guy can have more ducks. The reason they do it is because big oil companies lease their land out to hunting clubs. The hunting clubs go out and put “Posted” signs. So, then you got public lands that oil companies have control of because they bought it from the indigenous people over time; they've got the money to do it with. Because they operate in the business that's got 70 percent profit. They bought up the rights to these lands. They've subleased them to oil pipeline companies that move energy in and out of Louisiana. And then, on top of that, they've subleased it to hunting clubs, who become their private army that protects this land. Now, ain't that a great concept?

That comes at a price because it allows pollution to happen. So, when I go into a community, I connect with people. We don't need to talk about pollution in China. We've got pollution right here. And you talk to them about health. You ask them how many people in the family got cancer? How many people you know around here die young and what did they die from? That's how I connect with people. If I go talk to them about global warming, it doesn't resonate.

Aside from a social justice standpoint, is there anything intrinsic about the environment that you value?

If we don't stop polluting, we're going to have to go some other place to see a Great Blue Heron! That's the sad part about it. I don't think any generation has the moral or legal authority to pollute this space we live in for future generations. Nobody gave us that. And that most of the things we do now that we think that are so important are only temporary. You know, we're going to move on. We'll find another source of energy. The question is how much damage will we do until that happens. That's the million dollar question.

Some years ago, President Kennedy said, "We're going to the Moon." And I remember I was in middle school then, hearing the old farmers that came to our home in the afternoon talk about it. They were speaking Creole. They said, “What are you going to do on the Moon? They might mess up the rain, man! You watch what's going to happen!” They would speak with their concerns that it would disrupt the weather pattern. It was like, "This is crazy to go to the Moon. If God wanted us on the Moon, we'd have been there already." So, it challenged the world as we knew it.

That was a significant piece of movement, created a lot of technology. And it taught us to dream again that we could do the impossible. I think we need a redefinition, what is that pronouncement of the next big "We're going to the Moon?" I think it ought to be "We've got to clean the Mississippi River." As soon as we learn how to clean it, we'll be able to send water out to California. And we'll be able to send water out to Nevada, you know, just by learning how to clean water.

And then, we've got to stop acting dumb. The people in New York, they act all sophisticated. They're still dumping their damn trash in the ocean. Who gives the people of New York the right to dump trash in the ocean? I knew third world countries were doing it off the coast of Africa and in places like that, but New York City (is) still dumping trash in the ocean. That plastic isn’t going anywhere. It's going to have an impact on us. Why are they doing that? I mean, we're going to have to go after what's going into the ocean. We're going to have to stop and have a global law that makes it illegal to dump trash in the ocean. Why are we doing it?

There're some things that we're doing that are just stupid. And we've got to stop it. We've got to stop the stupid. We've got to stop dumping trash in the ocean like it's not going to make a difference. And we've got to stop filling the air with carbon-based pollution and benzene, thinking it's not going to make a difference. We've got to stop that. And we've got to stop polluting the water.

Do you think it’s our patriotic duty to take care of the environment we all live in?

I do think the ultimate definition of patriotism is service in your community. To understand that fellow citizens regardless of where, what country you're in the world, that the essence of all government is communities that are functional. After terrorists came in town, everybody got a gun. But as Shell come to town, they slowly kill you from sulfur dioxide, it ends up being OK because we've got jobs. That's the sad-ass story of this. You got me? Because they brought jobs.

We've got to come in to a better perspective of that, as we go from seven to ten billion people. When we go from seven to ten billion people, uh, everybody's going to want more stuff. But if you already look at the great inequity we have, about the seven billion people in the world, two billion don't have electricity still. Two billion don't have clean water in their homes and nearly three billion live on less than $4 a day.

And we come to a realization that the United States of America, we're less than five percent of the world's population. We consume 25 percent of the world's resources. So many people out there believe we are the Great Satan when it comes to pollution because we've got more stuff. A lot of us don't have one car, we have multiple cars, multiple televisions. So, if we consume 25 percent of the world's resources, how much of the world's pollution are we creating?

I think patriots take care of their community. They act where they live, that's been the history of our country. But I do think environmental protection is a part of our national security. When you go out and look at the National Security Council, the EPA director is not on it. He might be in the cabinet, but not on that Security Council. We've got to fix that. Since I moved back to Louisiana, we've lost three communities. People can't live there anymore. Grand Bayou, Bayou Corne, and now Mossville. And the fourth community has been marked, Belle River, people won't be able to live there for a permit that the state has just approved. That, that's a hell of a notion, you know, when you hear about some little bird in Africa is extinct. You read about it in the paper and it goes away.

When people start telling you about communities in Louisiana that people can't live there anymore because toxic air… In Mossville, ain't no birds left in Mossville. Why? Because they've surrounded it with 11 or 12 chemical plants. The birds don't go in there. The birds don't go near there. And they're down there as proud as hell of that. We've got all these plants. What's the asthma rate here? What's the rate of cancer? What's the life expectancy? Hell, they've got some good jobs. That's a dilemma. We've got to get that fixed. There's a perception that we can look the other way. We can no longer look the other way because it's affecting everybody.