Newsletter

Sign up and stay in-the-know about The Crowd & The Cloud and the world of citizen science.

My name is David Van Sickle, and I’m an asthma epidemiologist by trade. I’m Co-Founder and CEO of Propeller Health.

What inspired you to co-found Propeller Health?

Over the course of several years of studying asthma in different communities around the world, I was frustrated by a lack of timely and objective data about the disease. That limited the kind of public health work we could do, and where we could apply our interventions. I realized that this information gap was really affecting clinical care and treatment. We know a lot about the disease and how to treat it, but we haven't been able to change people's expectations. They don’t understand that they shouldn't be having symptoms very often, if at all, and that the medications we have today are actually pretty effective at prevention.

Inhaler with the Propeller Health sensor attached.

We got started back in 2006 building sensors that would attach to inhalers. Without the patient having to participate at all in the process, we would monitor how often someone was using this medicine. We know from the history of asthma epidemiology, that where people use their inhalers is really an important marker of what's happening in the community. There's a classic study from Barcelona, Spain, where it took about 10 years for a team of experts to understand that significant outbreaks of asthma were occurring, and even causing fatal attacks, due to a lack of appropriate filters in harbor silos.

When you reflect on that, it still is emblematic of how we do public health. We're waiting around for data to come in the form of a CSV file years later, and trying to understand what happened retrospectively. We realized there was this big chasm between what was being done in the public health sector, and what was being done with information and data in the rest of the economy. With these types of sensors collecting information from the bottom up, Propeller can close the gap.

Tell us a little bit about the Propeller sensor?

People with asthma, or any kind of chronic respiratory disease, are generally using inhaled medicines. How often somebody uses their rescue medicine, is actually a really important marker of how well they're doing. Chips, sensors, and radios have become small and cheap enough that they can now be physically built into the medications that people take. Our sensor attaches to an inhaler and tracks how often somebody is using it. With that information, you can then help monitor, teach and encourage them in using their daily medicine. The information is transmitted through a smartphone to the Propeller system where it's processed and analyzed, and sent back to the patient and physician, through different types of interfaces.

Propeller user, Christine Vaughn, logging her asthma data into the mobile app.

How do patients benefit from using the sensor?

One of the surprising things about asthma is that most people with the disease aren't doing as well as they could be. An important part of what we do, is help patients recognize when they need more help. By capturing this information about their use of medicines, we can provide back to a patient a very clear and useful picture about how they're doing, and ways in which they might improve. The idea is to help strengthen and support good, simple, self management of these conditions without adding to the burden of monitoring or managing the disease on your own. Today, we ask patients and families to keep track of their information in daily (written) diaries. The idea behind digital health approaches, like Propeller, is to make that go away. They don't have to think about it. They don't have to remind themselves or think through the fact that they're ill.

What type of data does the sensor actually gather every time it's deployed?

Simply, that the medicine was used, and the time and date that the medication was used. If the patient chooses, we can then send queries out to cooperating data services to ask for more information about what was happening around them at that point in time. Were they in a place with a high amount of air pollution? What was the temperature? Over time we can build up a picture of why they're having symptoms, and hopefully be there as a companion to help unravel this mystery of what's causing their asthma to worsen when it does.

How did the partnership between Propeller Health and Air Louisville come about?

A number of years ago, I met Ted Smith in Washington, DC as part of a Community Health Data Initiative. When Ted returned to Louisville to join the mayor's administration, he brought the idea for Propeller to the mayor, who recognized that there was an opportunity to put new technology to work for public health. We were able to launch a program to outfit residents of the metro area with the Propeller technology, so they could prove that people would be interested in capturing this information, and then sharing it with Metro Health and Wellness. That way they could think about evaluating and targeting what they're doing from a public health perspective about asthma.

With the history of poor air quality, and a high burden of asthma and respiratory disease, there was an opportunity here to use this information in a way that would hopefully give some insight into how that might be ameliorated with new interventions. The Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America has consistently ranked Louisville among one of the more challenging places to live with asthma.

You’ve said that Louisville is a good example of a closed loop in terms of research and policy. What do you mean by that?

Louisville presents a really interesting opportunity for us to capture information about how an individual is doing, and then to see that information go all the way through a loop of improved clinical care and treatment, and then to decision making and practice. What's important is that it's never going to be just this citizen effort, and citizen-collected data, but it's always going to be a complement to the great work that the Public Health Department is doing on its own to understand what's happening with the other half of the condition. We know that there's lots of small area, spatial, and temporal variation in what's happening with asthma, but we've never been able to capture it because we've never looked. It's never been visible before. Hopefully, the program will provide this technology to enough people in Louisville that we can really make some new and compelling insights, and new practices to alleviate it.

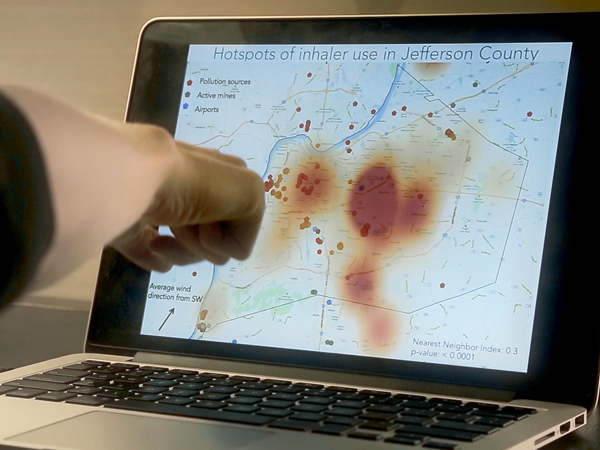

Map of data points from Propeller users showing asthma hotspots in Louisville.

What are “asthma hotspots” and why are they important to identify?

What we've been able to show is that there's a considerable amount of variability and variety in where people are having asthma symptoms. It's not just at home; it's at school, it's at work, it's out in the community somewhere. The data from the first wave of the program demonstrated that there were, despite our conventional wisdom, lots of places out in the community where people were having a significant number of events requiring them to use their rescue medication. Those hotspots really teach us quite a lot about what's happening with this mix of air pollution, pollen, and other exposures. That it's moving across the landscape in ways that cause people at one point to have symptoms, but then with wind, causes people in another part of the city to have attacks. It's much more of a dynamic, rich, robust profile of what's happening across time with the epidemiology of asthma, and it's that kind of information that can inform a more agile and rapidly responsive public health practice.

Why is it so important to have this crowd-generated data available and ready to then be represented in a geographical way?

If you think about the public health approach to understanding where asthma is happening, it's been really limited by the fact that the only geographic data point we have is the billing address where somebody who has an emergency room visit or a hospitalization comes from. It's really not taught us anything about where the attack began. Where the person lives doesn't mean that that's where their symptoms occurred or the exposure that caused symptoms. Propeller has always believed that there was more to asthma than just domestic exposures that were causing symptoms.

How can what a patient learns from the sensor, help them in a real world way manage their asthma?

There's really three ways that people who are using the Propeller system improve their management of asthma. One is by recognizing, for the first time in many cases, that their asthma is not as well controlled as they thought. Many people with asthma learn to accommodate or to tolerate symptoms, and don't realize that a lot more could be done to prevent them from occurring at all. That can provoke conversations with a physician about better use of the medications and so on. The other thing we can do is help people remember and be encouraged to use their daily medications that help them prevent the symptoms from occurring in the first place. Through reminders, education, support and encouragement, we can help people be more consistent users of that daily preventive medication. The third thing is, we can really help folks understand potential exposures that might be around them, so that they can take steps to avoid or mitigate those, and therefore give themselves a better shot at having a day without asthma symptoms.